Stansbury Park star parties offer a glimpse into the final frontier

When I arrive at the Stansbury Park Observatory Complex (also known as SPOC), near Tooele, Denise Larsen and Leslie Fowler, secretary-treasurer and vice-president of the Salt Lake Astronomical Society (SLAS), respectively, are sitting on a plush red couch, big enough to comfortably seat four. The red couch on wheels has been rolled out to the end of a cement platform—soon joined by an equally large and comfortable beige couch—and for a while, the outdoor lounge seems to be the focal point of social activity among the regulars at this star-gazing party.

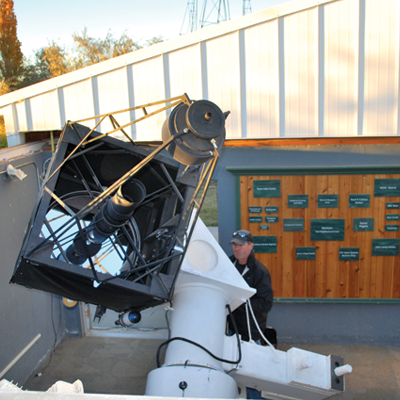

Of course, the clubhouse couches are only part of the attraction at the star party. A few feet from the portable sofas a gargantuan black steel structure that looks like a jungle gym dreamt up by Tim Burton points toward open sky. This is the Clements Telescope, named after its inventor and creator, SLAS member Mike Clements. It’s the newest of four telescopes that make up the observatory complex, and it’s a big draw for the bimonthly parties.

Stansbury Park Observatory Complex

The Salt Lake Astronomical Society began in 1972 with a group of astronomy enthusiasts who met on occasion to share their love of telescopes (and celestial objects) and kept in touch through a monthly newsletter. The club has grown in a lot of ways since its analog days (they now use Facebook and their website to stay connected). Membership is increasing, as is the society’s number of telescopes, and star parties attract more of the general public and a new crop of young enthusiasts.

The original telescope at the Stansbury Park Observatory Complex was housed in a classic white observatory dome with a sliding door on the rotating roof that pulled back to allow the telescope to extend out through the opening. When the society began constructing the complex’s new modern buildings in the early 2000s, they opted for a more practical design where the entire roof slides off on runners—leaving the telescope essentially inside of a four-walled cement box. The dome, with constant mechanical malfunctions that made it difficult to use, would have been scrapped except for a request from Tooele County.

“After so many years, they considered it a landmark,” Observatory director Rodger Fry says. “They offered us grant money for the new building if we promised to keep it.” The dome remains part of the slide-off roof over the Donna Pease Wiggins Refractory House (named in honor of the mother of SLAS board member Patrick Wiggins), and it’s still the beacon for newcomers. “Most people go straight for the dome and mistake the other buildings for park bathrooms,” Fry says.

Grim 32-inch Telescope

By 8:15, a good hour before dark, a dozen or so trucks, one motorcycle and one extremely classy red Tesla are parked on the lawn next to the cluster of SPOC buildings. Back trunk hatches are up and gate hitches down. Families are pulling out lawn chairs and fixing picnic dinners. Dads, mostly, are setting up tripods for the array of telescopes that are soon planted around the grass. One man is already seated in his lawn chair with binoculars in hand (you don’t always need to get fancy to have a good look at the stars), while his neighbor adjusts a telescope that looks like the astronomical equivalent of an Uzi—it’s got to be 8 feet long and, held up on a simple tripod, seems to be balancing on a wish and a prayer.

Fry explains that when the club was first looking for a place to have public events, Stansbury Park, a winding yarn of residential streets along the western flank of the Oquirrh Mountains, was appealing both for its dark skies and its proximity to the Salt Lake Valley. “People don’t want to travel more than 30 minutes for something like this,” he says. Tonight’s event has drawn a good 30 to 40 people, but it’s a slow night according to the regulars (they guess that the wildfire smoke is keeping people away).

Clements Telescope in front

of the Kolob Observatory Building

Larsen says there are usually enough people wanting to look through the new Clements’ telescope that they have to rope off the area and hand out numbered tickets to make sure that everyone gets their turn. When he built the scope in 2016, Mike Clements never imagined that his creation would be a main attraction at the star parties. A truck driver professionally, Clements thought up the blueprints for his telescope, a modified altazimuth-style Newtonian telescope (he altered the angle of the secondary mirror so that the viewer’s eyepiece is lower and easier to use), while on the open road. After testing the design with a prototype made of popsicle sticks, Clements, who never bothered to write down his blueprints, launched into construction.

The resulting instrument is impressive. The metal skeleton of the Clements scope stands over 12 feet off the ground at its highest point and stretches almost 20 feet from end to end. A reflector telescope, it uses a main mirror nearly six feet in diameter and a smaller secondary mirror to magnify objects by 150 times. The main mirror was manufactured for the federal government in the mid-1980s and valued at $1.5 million. It was originally intended to be part of a “space reconnaissance scope” designed to spy on Russia, but was decommissioned after developing a slight crack, which Clements says does not affect the functioning of the telescope. The magnification power is so strong that when Clements first looked at the moon and saw a blurry gray circle, he thought he’d made a design error. He soon realized, however, that instead of looking at the entire moon, he had zoomed in on one of its craters.

Daylight has dimmed and red glow-in-the-dark lettering on marker boards outside the observatory houses announce each telescope’s object of interest. Clements’ telescope is trained on Jupiter. The image is so crisp that you can see the stripes of rising gas on the planet’s surface (“speed stripes,” Clements jokes). People are still rotating through the lounge couches. In the nearby garage, where Clements’ telescope now lives, ’80s pop music is playing from a portable boom box and Larsen and Fowler have set up a table with free chocolate cupcakes to celebrate their birthdays.

As I pass the Wiggins observatory house on my way back to my car, I notice that a weather sign has recently changed. It now shows clouds and a frowny face. But even though the weather has moved, in no one seems in a hurry to pack up and leave. Carpe noctem.

Party Season Ends in October

The Salt Lake Astronomic Society (SLAS) hosts free public star parties from sunset until 11 p.m. every first, third and fifth Saturday at the Stansbury Park Observatory Complex. For detailed driving instructions, go to the SLAS website event calendar and click the details link on the Saturday Star Party event page.

There are also Friday night star parties at Wheeler Historic Farm in Murray, and at Harmons grocery stores around the Salt Lake Valley (check the website events calendar for details on exact locations). The star parties are seasonal events that run April through October. The final party for this year will be held on Saturday, Oct. 20, at the Stansbury Park Complex (in the Halloween spirit guests are invited to come to this final party in costume).

If stars and telescopes really get you going, consider becoming a member of the Salt Lake Astronomic Society. A yearly membership costs $20. It’s easy to purchase online at the SLAS website. The biggest perk for members is private access to the telescopes. Members who are interested can receive training on how to operate the equipment at the observatory and then, once trained, sign out any of the four telescopes for personal use.

Stansbury Park Observatory Complex

20 Plaza Stansbury Park

801-554-5849

SLAS.us