As one of Ogden’s unsung sons, it’s time to give Bernard DeVoto his due

Let’s begin à la Jeopardy. Category: Utah Literati. Here are five prompts:

- One of his history books won a Pulitzer Prize in 1948; another, a National Book Award in 1953.

- He was a recognized authority on Mark Twain.

- He was the greatest conservationist of the 20th century, according to Wallace Stegner.

- He wrote a monthly column, The Easy Chair, in Harper’s Magazine for 20 years.

- The first of his nine novels, The Crooked Mile, drew upon his experience growing up in Ogden.

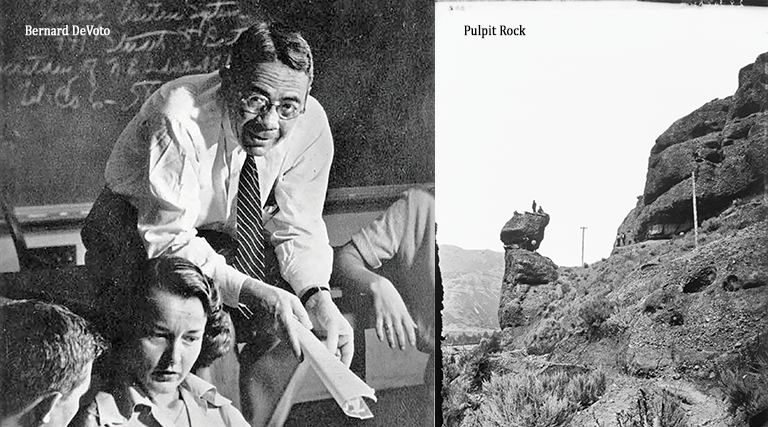

If you answered, “Who is Bernard DeVoto?” to all five, yours is an impressive sweep. Take a well-deserved bow! Not one in five Utahns even recognizes the name of Ogden’s accomplished man of letters. That he is not widely known might indicate a deliberate rejection born of the caustic essays that he penned about Utah and Mormonism early in his career. “Civilized life does not exist in Utah,” he wrote. The place is populated by “ruddy, illiterate, herd-minded folk” whose discourse is confined to “the Prophet, hogs and Fords.”

DeVoto was born in Ogden on Jan. 11, 1897. The town, Stegner has written, was split by “Homeric conflicts between the railroaders and the Mormons,” and DeVoto considered himself collateral damage. In seeking revenge, he disparaged the dominant religion in print: “These people are not my people, their God is not my mine. We respect, hate and distrust each other.”

“Benny” DeVoto graduated from Ogden High School in 1914. He spent a year at the University of Utah and then transferred to Harvard. Although a born-and-bred Westerner, he eventually adopted New England just as Stegner had done with Utah. “An apprentice New Englander,” DeVoto called himself. Although he was grounded in the Wasatch Front, “New England gave him a second belonging-place,” Stegner wrote.

He was a literary triathlete—novelist, journalist, historian. As a respected historian, his focus was the Rocky Mountain West. As a journalist, he practiced what Stegner called knight-errantry. DeVoto sallied forth from the pages of Harper’s and other national magazines to fight the fire-breathing dragons of the age—Sen. Joe McCarthy, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and the House Un-American Activities Committee. He wrote about censorship, civil liberty, isolationism and conservation. He was a champion of national parks and public lands, and he battled the ranchers who coveted them as grazing grounds for their sheep and cattle. He was also instrumental in stopping the Bureau of Reclamation from damming the Green and Yampa Rivers in Echo Canyon. Without DeVoto, Dinosaur National Monument would have shared Glen Canyon’s watery fate.

His death in 1955—a year before Edward Abbey went to work in Arches National Monument and the year Terry Tempest Williams was born—ended a career that was “flawed, brilliant, provocative, outrageous … often wrong, often spectacularly right, always stimulating, sometimes infuriating, and never, never dull,” Stegner wrote in The Uneasy Chair, his 1974 biography of DeVoto.

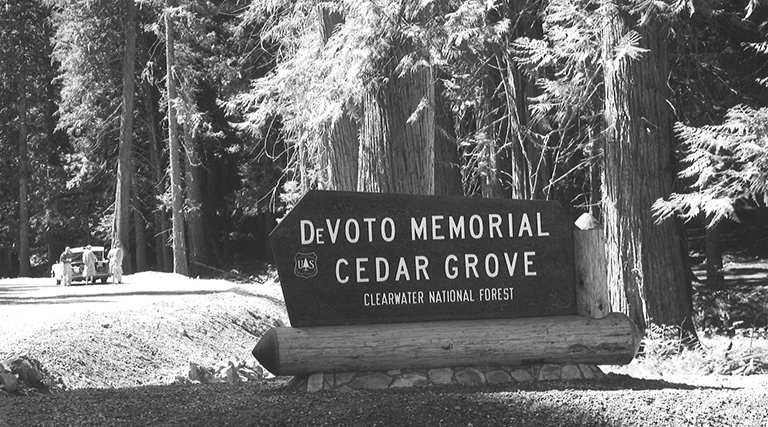

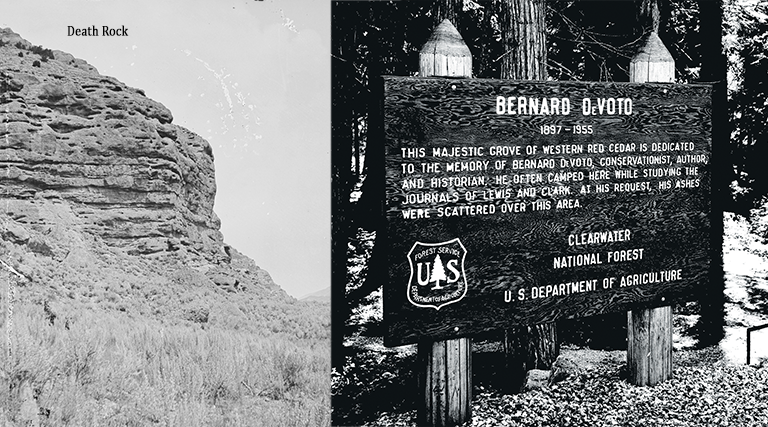

If you set out in search of more answers to the question, “Who is Bernard DeVoto?” a visit to his hometown will not be helpful. His house at 2561 Monroe Blvd. has been supplanted by the sprawl of an elementary school. No one in the tourist office or the library has ever heard his name. Ogden High School’s commemorative plaques don’t include one for him, and the school library owns none of his 21 books. To find a memorial, you must drive 500 miles to Idaho. There—on Highway 12, 42 miles west of Lolo, Montana—an old-growth stand of Western Red Cedars on the Lochsa River was dedicated in 1962 to Utah’s celebrated “conservationist and historian of the west.”

Perhaps it is time for Utahns to reconsider the cold shoulder turned on the man Stegner called “the most distinguished writer who ever came out of the state.”

DeVoto tried to make amends decades ago by recanting his criticism of Utah. His self-imposed exile from Ogden, which began at age 25, caused him to re-evaluate his first belonging-place. His denigration of Utah was “ignorant, brash, prejudiced, malicious and what is worst of all, irresponsible,” he concluded in his 50s. Nevertheless, his contrition fell on deaf ears. DeVoto’s legacy was sown with salt even as the sins of others like Edward Abbey were forgiven.

You would expect Ogden to favor reconciliation. It is no longer the rough-and-tumble railroad town that gangster Al Capone steered clear of. It has cultivated a “mountain-to-metro personality,” its website explains. The change seems a welcoming development for DeVoto, himself a mountain-to-metro scholar and writer. Who’s to say that Ogden would not profit from another bronze statue on 25th Street? A DeVoto Center at Weber State University? A plaque in the library of Ogden High School? An exhibit at Dinosaur National Monument? Is there no place of honor for a 20th Century “public thinker” in a post-truth age?

Besides public thinking, DeVoto was an environmentalist before the word was coined. His activism stands him in good stead with like-minded Utahns in 2019, a validation of Stegner’s belief that his articles would be instructive to future generations. His issues, tenacious as Bull Thistle, are their issues. Sixty years later, water is no less valuable in the drought-prone West; wilderness is no less threatened by agents of commerce; politicians are no less venal, and no less than $11 billion is needed to fix the maintenance problems at Bryce, Arches and the rest of the national parks.

Good fortune has given Utah a landscape like no other. Even with the integrity of the state’s public lands in jeopardy in 2019—even as dams, pipelines, coalmines, ATV tracks and oil wells have tireless promoters—DeVoto is as instructive as Stegner hoped he would be. “One cannot be pessimistic about the West,” Stegner wrote. “This is the native home of hope.”

Who is Bernard DeVoto, then? A distinguished Utah native whose legacy ought to be a source of hope—and pride.