Utah’s celebrated kayaking expert wrote the book on Utah river running.

Every spring, Utah’s snowpack melts and tumbles down a million rivulets, into thousands of creeks that form hundreds of rivers—an annual procession—the velocity and magnitude of which is noted on obscure government maps and websites in the form of “cubic feet per second.”

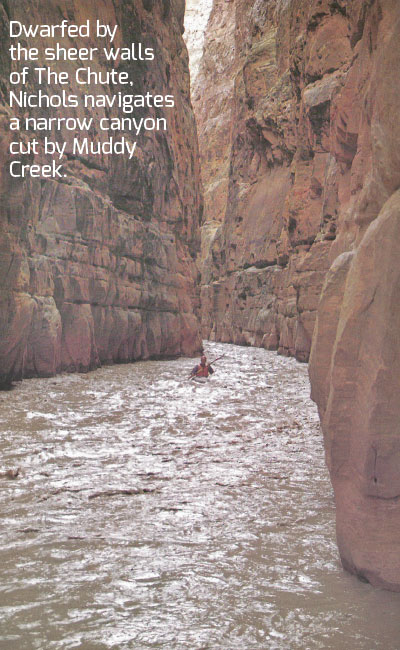

Assuming you have a plastic boat, a paddle, assorted safety gear and sufficient know-how, little-known streams like Ferron Creek, Chalk Creek, Cottonwood Creek and Muddy Creek—as the numbers attached to them rise to, say, 400 cubic feet per second (cfs)—could be floated.

But what then? What if the number next to Cottonwood Creek reads 1,000cfs? Maybe Cottonwood Creek is actually just a ditch, or maybe ranchers have strung barbed-wire fences across its surface, or there’s a human-killing logjam halfway down the sucker that can’t be avoided. Maybe.

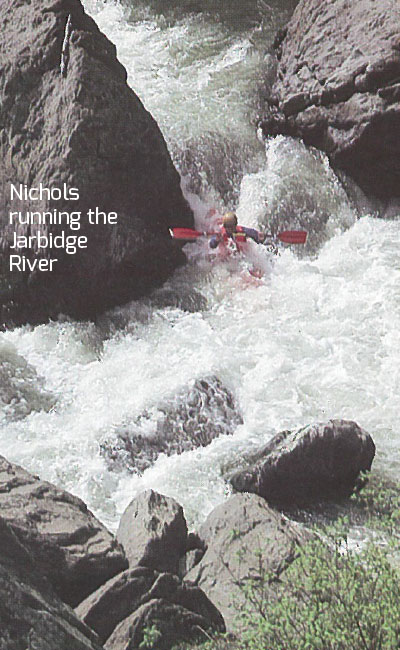

In the late 1970s, there was one source to turn for information about the conditions present on nearly any stretch of Utah water: Gary Nichols, a kayaking instructor at the University of Utah who, inspired by a pure love of seeing new places, had for years endeavored to kayak down every stretch of boatable water in and around Utah. And so, a call to Nichols was prudent before striking out to explore an unfamiliar stretch of whitewater.

“My goal in kayaking,” Nichols says, was “to do something new all the time. I was trying to do that.”

“My goal in kayaking,” Nichols says, was “to do something new all the time. I was trying to do that.”

Nichols found a book that listed all of the stream flows in Utah, noting each one that had a flow of 400cfs or higher, and he struck out to explore each of them. As word spread about Nichols’ efforts, his phone began to ring.

“People started hearing I’d been somewhere they hadn’t heard of, so they’d contact me and say, ‘Why don’t you write a book so we have access to it?’” Nichols says. “At first, I didn’t want to do that, but after enough requests, I finally just wrote a book and self-published it.”

That book, River Runners’ Guide to Utah and Adjacent Areas, first published in 1982, remains in print, most recently updated in 2002 and published by University of Utah Press. It continues to be the most comprehensive guide to kayaking in Utah.

Shortly after the first edition was published, the West saw several years of massive snowpacks and spring runoffs—a time that allowed Nichols to run a few stretches of wild rivers that today are little more than 2-feet-wide dry washes, choked with brush.

“I had great fun during the high-water years,” Nichols, now 65, says. “There are a couple of rivers I got on that I don’t think have ever had water since.”

For the purposes of kayaking, Nichols explored some uncharted territory, paddling and documenting numerous first descents, one of which, loosely known as Cottonwood Creek, remains his favorite stretch of whitewater in Utah. A section of it that flows out of Joe’s Valley Reservoir and along Highway 29 toward Castle Dale bewitched Nichols. The challenging drops and hulking boulders mid-stream provide a kayaking experience unlike any other in the state, Nichols says. The allure of Cottonwood Creek was increased, and it continues to be noted by boaters to this day for its unique aquamarine color, making the run as beautiful as it is challenging.

“That was one of the places a friend of mine and I discovered in the early high-water years in the ’80s,” Nichols says. “We had never heard of it. We went down there and hit a bunch of rivers that came out of the Wasatch Plateau and couldn’t believe it. There were just incredible rivers. We thought we’d died and gone to Idaho or somewhere.”

The most challenging stretch of water discovered by Nichols was a place called Sixth Water, an artificial river created by a tunnel that delivers water from Strawberry Reservoir to points west. Sixth Water, Nichols says, was given the distinction of being the first true Class V (the most difficult classification of whitewater) in Utah by one of Nichols’ pals who accompanied him.

Sixth Water, as Nichols knew it, was short lived, though. A new tunnel was built that delivered water to a lower section of the river, effectively de-watering the stretch that Nichols had found so challenging.

While the impact of Nichols’ book is hard to gauge, his influence on the sport of kayaking in Utah is perhaps best measured through his teaching. Since 1978, Nichols has taught a kayaking course at the U of U. During these 38 years, Nichols estimates he has taught more than 10,000 people the basic Eskimo roll—a fundamental skill that is to kayaking what tackling is to football.

Over these years, Nichols has watched the popularity of kayaking ebb and flow. The sport, he says, seemed to peak in the early 2000s, reaching a low in the lead-up to the Great Recession, when Nichols went from teaching four classes with 20 people in each class to one class with 10 people. In recent years, though, Nichols says more people seem interested in learning to kayak. This spring, he taught two beginning kayaking courses.

Over these years, Nichols has watched the popularity of kayaking ebb and flow. The sport, he says, seemed to peak in the early 2000s, reaching a low in the lead-up to the Great Recession, when Nichols went from teaching four classes with 20 people in each class to one class with 10 people. In recent years, though, Nichols says more people seem interested in learning to kayak. This spring, he taught two beginning kayaking courses.

Although the sport is well represented on the pages of Outside Magazine, with shots of kayakers hurling themselves off 100-foot plus waterfalls, Nichols says kayaking is a great sport for anyone who loves being outdoors and exploring hard-to-reach places.

“I try to tell them it’s just one of those things you can do the rest of your life,” Nichols says. “It’s a great way to stay active, and it gets you to places that you may have a hard time getting to otherwise. From there, you can make it whatever you want. You can stick to easy, scenic, beautiful places; you can do moderately hard, you can do as hard as you want. It just has unlimited potential.”

During his time as a kayaking instructor, Nichols says he’s taught multiple generations of families to kayak. As he passes kayaking skills down, certain chapters of Nichols’ book act as an epitaph to wild places that have either been destroyed by man, or that are no longer favored by a natural world under assault by warming temperatures.

This is another lesson that any person who has bobbed down a river in a plastic kayak can attest to: Rivers are delicate and unreal places that can easily be wrecked by the whims of developers, government engineers and politicians.

In the 1986 revised edition of River Runners, Nichols, whose modest soft-spoken nature seems to run counter to the list of burly first ascents he notched while exploring Utah, extolls the importance of exploring, appreciating and coming to know hard-to-reach places in the world. The context involves a stretch of the Virgin River between the towns of Virgin and La Verkin, which was lost to a water project.

“The river is now buried in a pipeline and the deep, beautiful canyon has been desecrated by construction. The many animals and birds, including some bald eagles, will have to move elsewhere to find the life-giving water that has been stolen from them,” Nichols writes. “A couple men are richer; the rest of us are poorer. Hopefully, revising this guide will make more people aware of the variety of rivers found in Utah so that, through awareness, we can work to preserve them. Maybe future development projects will not slip by as unnoticed as this one did.”