The river odyssey of explorer and scientist John Wesley Powell gave the West a voice and a water advocate

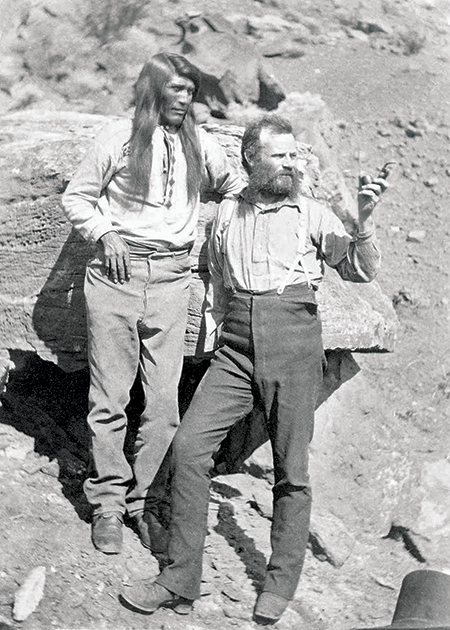

This black-and-white picture is certainly worth a thousand words (Or, in the case of this article, 750 words—my allotment). But its real value should be measured in miles. A thousand, to be exact. This is the distance the bearded man to the left traveled a century and a half ago.

His name is Major John Wesley Powell. Next to him is Tau-gu, great chief of the Paiutes. They are seen here posing for photographer John K. Hillers. This 19th century photograph is both intoxicating and illuminating, not just for the historic explorer it shows, but also for how he changed the West.

The picture is one of many in a new book by Carol Ormond, called The People: The Missing Piece of John Wesley Powell’s Expeditions. The book’s release comes on the 150th anniversary of Powell’s landmark expedition into Southern Utah. Ormond tells me that, “Maps in 1869 showed a blank space of territory approximately the size of Connecticut, Delaware and Rhode Island combined that had yet to be explored.”

Drawn to that blank space on the map, Powell set out from Green River Station in the Wyoming Territory on May 24, 1869. Accompanying Powell were nine other intrepid souls. Traveling on four wooden boats, their goal was an audacious one: to explore the Great Unknown, a section of country that remained a mystery. Only six men were barely alive by the end of the journey. Powell went on to map river drainages of the arid West, advocating to Congress and policymakers the need for sustainability and stewardship.

“I think Powell was an explorer and fascinated with the West as a place,” Tom Minckley, an University of Wyoming geography professor, says at a recent gathering for Powell’s 150th anniversary. “The question of the Great Unknown was out there, and he was the right person to look for an answer.”

This wasn’t an expedition for the faint of heart. Using boats not particularly well-suited for the journey, Powell’s adventure took him and others down the Green and Colorado rivers, where they became the first to explore the watersheds in their entirety.

“The trip was considered so dangerous and impossible,” Ormond says, “that Powell read about his and his crew’s demise in local newspapers all the way back East.”

But we now know reports of their demise were greatly exaggerated. Three months after setting out, Powell’s perseverance was rewarded when his expedition reached the Grand Canyon. However, along the way, a third of Powell’s original crew departed from the grueling mission.

I ask Minckley why, 150 years later, people should remember John Wesley Powell. In addition to surviving the journey and his feats of daring-do, Minckley points to the lasting impact that the Powell Geographic Expedition had. He feels the 1869 trip helped establish Powell as a critical voice for the West and its resources. This voice, Minckley argues, helped guide a vision for the future of Western expansion.

Ormond agrees. “Travelers, tourists and residents of the area today are all benefactors of Powell’s scientific surveys,” she says.

She goes on to explain how, in later years, Powell returned to survey, map and photograph the areas he explored. In fact, the photo of Powell and Tau-gu is from 1873 (Powell did not have photographers working with him on the 1869 expedition). Fittingly, Ormond’s book pays homage to the Native Americans whom Powell encountered on his adventures and the help they gave him.

Seven score and 10 years after the initial expedition, the photograph of a one-armed Civil War veteran named John Wesley Powell and Tau-gu, the great Paiute chief whose tribe lived on the Virgin River, is still worth a second look. It has the power to take us back to the Wild West and to the Great Unknown. But the picture also very much points to the future.

Powell’s 1869 expedition passed through what would be become some of Utah’s most cherished places, including the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, Dinosaur National Monument and Canyonlands National Park. In fact, many areas are still called by names Powell’s exploration bestowed upon them: Winnie’s Grotto, Whirlpool Canyon and Split Mountain.

Author Ormond mentions another signature Utah landmark, one that is a household name but, upon reflection, conjures up the lingering image of a man, a time and a historic journey. “At the very least,” she says, “houseboaters should honor Powell’s memory by remembering that Lake Powell is named after the great American explorer John Wesley Powell.”

One thousand miles and 150 years later, this is a fitting image to end with.