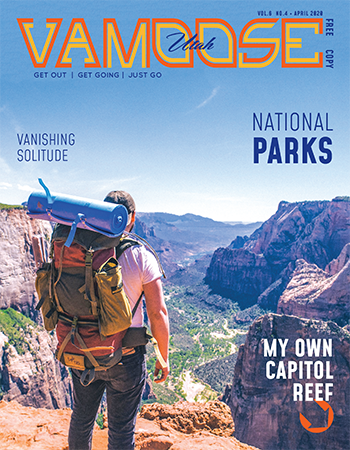

The joys of a life

dedicated to ascension

At 230 feet up a desert tower, halfway through a classic climb and wedged between a rock and, well, another rock, I start to wonder how most people spend their weekends.

I imagine they relax at home, maybe go for a walk through the park with their families or spend time in a city drinking, eating and laughing. They probably use vacation days for actual vacations—like tropical getaways, big cities and the occasional cruise.

My knee slips out of the wide crack I wedged it in, bringing me back to my current predicament. If it weren’t for my shoulder jammed in that same crack, and now holding my entire body’s weight, I would have fallen past the last piece of protection I placed 20 feet below me. Nothing to panic over, however: I simply re-wedge my now-bloodied knee back in the crack, wiggle my body up a few feet and clip an old rusted bolt that some dirtbag drilled in the tower’s sandstone years ago.

Now safe-ish, I let out a satisfied smile, because this is my vacation, and I continue up my “cruise.”

Most people look perplexed when I tell them about the climbing lifestyle—with good reason. What part about waking up before sunrise, hiking miles of steep terrain and bleeding your way up a rock wall sounds like a pleasant time away from work? Let me tell you.

In the early 1900s, a mountaineer named Lionel Terray called climbers “Conquistadors of the Useless,” because that’s exactly what we are. We spend the majority of our lives fighting our way to the tops of mountains, just to stand in that lonely place, turn around and go home.

In the early 1900s, a mountaineer named Lionel Terray called climbers “Conquistadors of the Useless,” because that’s exactly what we are. We spend the majority of our lives fighting our way to the tops of mountains, just to stand in that lonely place, turn around and go home.

Every climber will give you a slightly different answer if you ask them why they climb. Boulderers admire the physical exertion and mental effort involved with projecting short, yet challenging, rock problems. Traditional climbers tend to romanticize the sublime beauty found in ascending multi-pitches on big walls. Regardless of each climber’s style, I believe every ascender gets a personal sense of accomplishment in escaping their everyday lives and interacting with the outdoors this way.

One of Utah’s most famous adventurers, Author Edward Abbey—who, in his own words, had a “lifelong love affair with the rock”—felt this personal sense of accomplishment during his many adventures in Arches National Park.

In his book Desert Solitaire, Abbey tells tourists to “crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbush and cactus. When traces of blood begin to mark your trail you’ll see something, maybe.” Abbey explains that we have to go through some sort of physical effort, and even make a painful sacrifice, in order to see nature’s true self. I like to assume the “something” Abbey sees is the same sense of accomplishment climbers feel when we’re standing on summits. Our sore muscles and torn-up hands signify the price we pay to see what Abbey saw and felt.

There really isn’t a more sublime place than a summit. Tied to bolts, chains, trees or boulders, my climbing partners and I extend our gaze farther than ever. We see the Wasatch Range continue into the unknown, with summits beyond summits begging us to climb them next. We watch birds dance in the air and sometimes swoop down to get a better view of us humans here on the peak in our unnatural habitat. The still silence found on each summit conveys a serene feeling, while winds blow against our skin, reminding us that we’re living instead of dreaming. We see how large nature is and how small cities are.

Like the small city below, all of life’s problems seem to dwindle on the summit. This escape is essential to my well-being. Climbing is one of the few things that can diminish my stress in life, by making me focus solely on the task at hand.

I’m not the only one. Many climbers dance on rock because it helps with depression, anxiety or the blahs associated with the humdrum of life.

So if you’re looking for a healthy and natural way to overcome life’s everyday stresses, look to the nearest rock outcropping and search for a climber: We’re pretty easy to spot. You can usually find us on hiking trails, covered in dirt—or blood—with big backpacks on or mattress-size crash pads strapped to our backs. We’re just about always smiling. We’d be happy to show you what Abbey saw, give you that natural escape and help you find a personal sense of accomplishment unlike any you’ve felt before.