Discover the true meaning of wilderness floating the Green River’s Desolation Canyon.

There are times when the outdoor experience doesn’t seem all that special. Maybe it is the rumble of a generator at 5 a.m. coming from the neighboring camp spot, or the packs of whining ATVs that shatter the solitude of your favorite hike. Or maybe it’s just too many people enjoying what our great state has to offer.

There are times when my soul aches for quiet isolation away from all the hubbub, and in those moments, I find myself turning to Desolation Canyon—a 90-mile stretch of the Green River in eastern Utah known by river enthusiasts as merely “Deso.”

The canyon earned its moniker nearly 150 years ago when John Wesley Powell laid claim to being the first white man to float the length of the Green (he probably wasn’t, but that’s another story). In the intervening decades, the canyon corridor has remained largely untarnished and undeveloped, and in 1969, on the 100-year anniversary of the Powell Expedition, about half of the canyon was designated the Desolation Canyon National Historic District to reflect these unspoiled characteristics.

Deso is currently the largest wilderness-study area in the lower 48 states—a prized jewel in the campaign for Utah wilderness. Oil-and-gas developers must keep sufficiently distant that the sights and sounds of their rigs do not impact the tranquility of the river corridor.

In other words, once you float away from the Sand Wash boat ramp (commonly accessed from the Myton turn-off on U.S. Route 40, just east of Duchesne), you will not see or hear the outside world for the next four or five days (there are no roads). Chances are you won’t see very many people, either (the Bureau of Land Management limits the number of people of the river at any one time).

You also won’t be interrupted by your cell phone (no service) or kids playing video games (no way to charge batteries).

Deso is a float trip through millions of years of jaw-dropping geologic history and thousands of years of human history. There are places where the canyon is more than a mile deep and maybe only half that wide. Bighorn sheep watch you disinterestedly from the cliff ledges as you float by, and pelicans dive in the murky brown water around you. About the only sounds you hear are the occasional slap of a beaver tail and the welcome pop of a beverage can on a hot summer day.

If you are, as I am, fascinated by the ancients who once called this home, there are dozens of places to camp or break bread along the way that reveal traces of the ancient farmers. You’ll see rock-art images pecked and painted on the canyon walls and granaries tucked on the cliff ledges. It’s a great reason to spend time exploring, because discovering them is half the fun. Also, there are river guidebooks that offer some clues; my favorite is Desolation River Guide (WestwaterBooks.com/products-page/river-guides/desolation-river-guide).

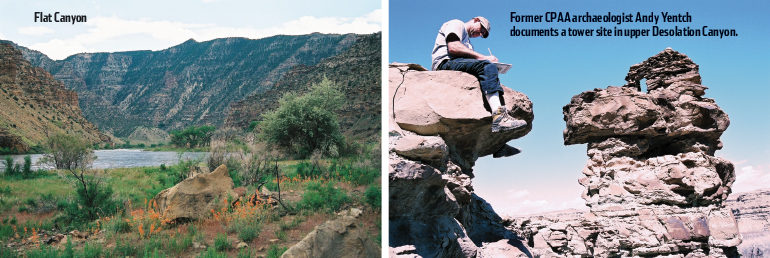

Every side canyon offers discoveries of something glorious. In the spirit of this remarkable isolation, you feel as if you are the first to ever discover it. You could spend days exploring Range Creek, Flat Canyon and Rock Creek.

I have logged nearly 30 Deso trips, mostly as part of my archaeological research. And each and every time, without exception, I have pulled off the river at Swaseys Boat Ramp with a renewed feeling of discovery. Here are a few ways to experience Deso:

- For river novices, it’s best to use a commercial outfitter, and there are lots to choose from. I have worked closely with Sherri Griffith Expeditions (GriffithExp.com) and Colorado River & Trails Expeditions (CrateInc.com) and can vouch for their environmental ethics on the river. These folks care passionately about our public lands. They also handle all the organization and cooking. It can be pricey but worth every penny.

- Another popular way to enjoy the river is by self-support kayak or inflatable canoes (rubber duckies). The dozens of rapids found here are not monsters like you’d find in the Grand Canyon, but they are technical. You need to know what you are doing. And you will be required at check-in to prove you have all of the required gear for safety, first aid, self-rescue, human-waste removal, etc.

- And last, organize your own float trip with your own tribe of friends. If you or your friends don’t have rafts, you can rent from university outdoor shops. River permits for private trips always sell out on Recreation.gov. But, if you can be flexible on your dates and wait until a month or so before you want to go, there may be cancellations (about a third of permits cancel), so chances are good you can snag a trip. For information on permits, visit Recreation.gov at bit.ly/2iEYtN1

You should plan on at least five days on the river, though, seven is better. You won’t have a clue as to what happened in your absence, and you won’t care.

Jerry Spangler is executive director of the Colorado Plateau Archaeological Alliance, a nonprofit that advocates for protection of archaeological sites on public lands in Utah and other Western states.