The Hayduke Trail is a demanding hike—one that might have made Edward Abbey proud.

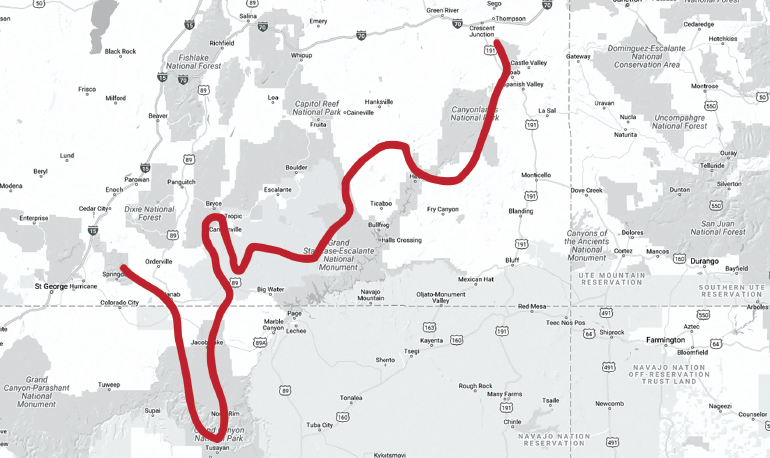

The Hayduke Trail, named for the crotchety desert outlaw in Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, is a remote, logistically complex and physically demanding long-distance hiking route. The trail twists through six national parks in southern Utah and northern Arizona, totaling 812 miles of parched, rugged desert landscape. The route-finding is challenging, the shade is scarce and the trail signs are nonexistent.

Hayduke Trail (HDT) logistics can be intimidating. Erin “Wired” Saver, an accomplished long-distance hiker and Triple Crowner (hiker slang for someone who has walked the 7,600 combined miles of the Pacific Crest, Appalachian and Continental Divide trails) explains it this way in her 2015 Hayduke trip report: “The planning of this hike is on par with the endurance needed to hike it. The Hayduke is definitely not a comfortable trail.”

Water on the HDT is especially troublesome. Jonah Katz, who spent just over 500 miles hiking his version of the Hayduke in 2016, said this: “You can’t just hope to find a pothole of water out in the sandstone, because it’s simply not going to happen in 100-degree weather.” Multi-day treks between reliable water sources are common on the HDT, and Katz said that during his hike, he was usually carrying between 8 and 14 liters of water—which meant that, on the heaviest days, he had 30 pounds of water in his backpack.

But every year, a select group of explorers shoulder their packs, take a final look at their resupply plans and head south to hike their own version of the HDT. And Joe Mitchell and Mike Coronella were first.

In 1998, Coronella and Mitchell “were two ski bums who had no experience at all in long distance hiking,” Coronella., speaking by phone from Moab where he now runs a guide company, says, “Neither of us had ever done any long through-hiking. We had no idea what we were doing, so we just decided to go wander.”

Mitchell, now owner of a fly-fishing outfit on the Provo River, was the trail’s route-planning mastermind. “I really love maps,” he concedes. “That was my job as part of our hiking partnership, figuring out where to go and whether or not it would work.” After finishing their first hiking circuit, 98 days in the backcountry from Arches to Zion, Mitchell and Coronella immediately began planning another trip—and in 2000, added on a second section that included the Grand Canyon. Spliced together, those two hikes formed the HDT as it’s outlined in their 2005 guidebook, The Hayduke Trail: A Guide to the Backcountry Hiking Trail on the Colorado Plateau.

Both Mitchell and Coronella seem a little dumbstruck by the trail’s evolution. “The trail has a life of its own,” Coronella says. Mitchell agrees, “I love that it’s sort of a sleeper trail, mostly underground. Some people really want to follow the guidebook, but most people who hike the Hayduke add variations and adjust it to their own needs, and that’s how it should be in my mind. The trail isn’t a sidewalk.”

Jonah Katz, reflecting on his time on the trail, concurs. “This isn’t a set and fixed route,” he says, “We had fun with it and went where we wanted to go, and I think that’s the message in the guidebook: This is the way we did it, but you should find what looks good to you.”

“The Hayduke connected all these different places I had gone hiking as a kid,” Katz continues, “And I thought, what a great hike to do as a Utahn, as a way to mentally connect together all these places, places that are disparate when you drive to them and then drive home.”

Unique among many of the long hiking trails in the United States, all 812 miles of the HDT are on public lands. Coronella and Mitchell are both passionate about conservation and access, and Coronella continues to work with the Utah chapter of the Sierra Club. “We need to let our elected officials know that our public lands are important to us,” he says, “and that we will not stand by and watch [them] be taken away.”

The HDT is not for everyone—but for Coronella, exploring the deserts of southern Utah is a worthy practice no matter which corner you end up in. “Every time you come around a corner in the desert,” he says, “you see something you never dreamed of.”

Journal of My Journey: Lower Muley Twist trip report

I’m hiking Lower Muley Twist alone, my first day out this year, on a spring afternoon under cloud-streaked skies. It’s been a long, un-aerobic winter, and my body feels a little baffled by the dumb, animal demands of backpacking. The trail past Cottonwood Tanks is all sand and sharp snags of sagebrush, and my newly acquired trekking poles feel desperately awkward. I can’t figure out how to hold them, and I think too hard about which stride goes where—left foot/right pole, right foot/left pole. I become hopelessly discombobulated, stutter-stepping in an attempt to catch up with myself. Through the sagebrush, I watch a black-tailed jackrabbit rocket toward the horizon.

The first evening, I camp by Halls Creek, nestled back against swelling sandstone domes and the bright, sudden sunset exploding behind them. In the dark, I attempt to read Edward Abbey and poke my head out the tent zipper occasionally to check on the night. The sky isn’t black or indigo but instead a kind of liquid blue, plush with stars, the only sounds the whispers of the synthetic fabrics swathed around me. Ed says, “I am 20 miles or more from the nearest fellow human, but instead of loneliness I feel loveliness. Loveliness and a quiet exultation.” I sleep deep and hard, dream of nothing.

Spending days and nights in the Utah desert is intense—it’s nothing like the Sierra Nevada, the Wasatch, or the Uintas, soft green mountains with clear fresh water everywhere you look. The mountains are infinitely more forgiving—beautiful, but far less demanding, happy to serve you just one more Alpine lake, another brook babbling with snowmelt, another patch of shade. The desert slaps you in the face, requires your full attention—here, your missteps mean something.

And at the same time, the desert meters out these moments of wild, private magic. It rewards you with solitude, with perfect late-afternoon light, with tiny bats ricocheting across a fluorescent pink sky at sunset. Hours before I shuffled back to the car, increasingly dehydrated from a misjudged water carry, Muley Twist peeled back into a side canyon. There, tucked in the shadow of the sweeping slickrock walls, was a pothole deep and green enough that I could slip my whole body inside, red mud slick on my skin, up to my ears in cool water, giggling at the luxury of it all. The desert doesn’t cut you breaks, but it’s a fair trade—water only feels like magic when you have to work for it.

Desert Climate Control: An Endorsement of Sun Shirts

As summer settles over Utah’s deserts, keeping cool becomes a challenge—and even with plenty of water and sunblock, sometimes the best solution to sun protection is simply covering up. After years of avoidance due to the undeniably goofiness of sun shirts, I’m now officially a convert—nothing will keep you cooler or protect you from sunburn more effectively as the desert days get longer, hotter and more intense.

As a general rule, the more ridiculous you look while wearing a sun shirt, the more effective it is. Don’t be fooled by the potential charms of bright colors or loose-fitting hoods— the best sun hoodys are the ones that make you look like a deranged, fly-fishing ninja. Stick to light colors (white is best, even if it looks disgusting after a week in the field,) and elasticated or cross-over hoods that protect your chest, neck, and ears.

I wear Patagonia Women’s Sunshade Hoodys—they’re lightweight, comfortable over multiple days out, and effective. This model does have an unfortunately placed zipper pocket that tends to rest right under the hip belt of your pack when backpacking, but I’ve found that some quick adjustment after you buckle up prevents any chafing. The best thing about wearing a sun shirt (besides fashion, of course) is it means you can forgo sunblock everywhere except your face—a small mercy when you’ve been out for multiple days and the thought of rubbing thick, greasy lotion into all your exposed skin makes you want to weep. And with desert summers, any opportunity to keep the sun off your skin is one worth taking.