Rock art of Barrier Canyon inspires awe.

I have spent nearly a half century tiptoeing among the remnants of the ancient Americans—their cliff dwellings and pit houses and granaries and rock art. And I have never lost the feeling of awe that comes from imagining what life was like for them millennia ago.

But of the hundreds of places I have visited during my career as an archaeologist, Horseshoe Canyon is uniquely different. Here, the ghostly, life-size images painted on the canyon walls actually seem to be staring into my soul. It is an eerie, magnificent experience unlike any other, and well worth the 7-mile day hike.

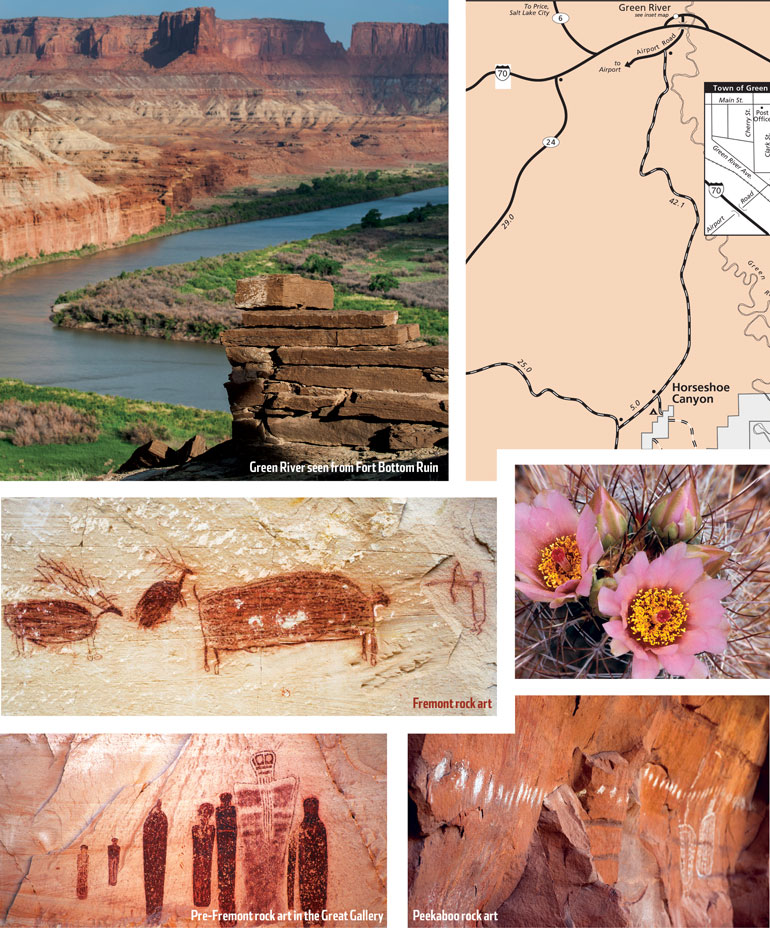

Horseshoe Canyon—some archaeologists, myself included, actually prefer its original name, Barrier Canyon—is a minor tributary to the Green River located in the middle of the San Rafael Desert. It is beautiful, certainly, with the sheer sandstone cliffs and a ribbon of cottonwoods marking the canyon bottom. But it is also rather unimposing by the standards of Utah’s canyon country.

What makes Horseshoe Canyon unique among Utah’s many archaeological treasures is its mystery. Why is some of North America’s most impressive Pre-Columbian rock art nestled here in this small out-of-the-way oasis in the middle of the Utah desert? When were these images created? Who made them? Why?

Quite simply, archaeologists do not have a lot of definitive answers. It has long been assumed these images—referred to as the Barrier Canyon Style of rock art—are very, very old, perhaps even 7,000 years old.

Archaeologist Betsy Tipps re-examined the data from numerous Barrier Canyon Style sites in the Canyonlands region, and she made a very convincing argument they were probably made between 1900 B.C. and A.D. 300 by Late Archaic hunters and gatherers before the arrival of agriculture. Polly Schaafsma—one of the leading rock-art authorities in the West—narrowed it down further, to between 500 B.C. and 500 A.D.

But a few years ago, Utah State University archaeologist Steve Simms and his colleague, geologist Joel Pederson, turned all that thinking on its head. Using a geologic technique called optically stimulated luminescence (much too complicated to explain here), they derived three dates, all at 1100 A.D., or the height of the much-later farming culture known as the Fremont Complex. Even allowing for a generous range of error, the images would certainly not have been painted before about 1 A.D.

Utah rock-art enthusiasts did not take kindly to those findings. They point to the character of images at Fremont rock art sites that commonly feature the bow-and-arrow and rigid human figures. The more-fluid Barrier Canyon Style humans, usually with no arms or legs, are never depicted with the bow-and-arrow, a technology that did not appear in this region until about 100 A.D. And hence, the Barrier Canyon images must pre-date the Fremont farmers.

The debate rages on. But most importantly, the USU study has stimulated new conversations about the past. Could it be that the ghostly rock-art images found here represent a mixing of iconography and ideology of Archaic foragers and the first farmers migrating north of the Colorado River? Could it represent the world view of many different groups through time, each one adopting the past while reformulating it to conform to their own life experiences?

The slower you go, the more you see

Most who visit here make a 3.5-mile beeline to what is known as the Great Gallery—the largest concentration of these ghostly images anywhere on the Colorado Plateau. And most never slow down to notice the dozen or so small sites along the way, each exuding mysteries of their own.

Trail guides all say it takes a good five hours to hike to the Great Gallery and back out to the trailhead. But it takes a full day to really appreciate this canyon. Just past the point where the trail reaches the bottom of the canyon is a series of small Fremont figures painted in bright red. And about every quarter mile beyond that on both sides of the canyon are small groups of Barrier Canyon Style images that are rarely noticed.

The slower you go, the more you will see. And the more you will feel the ghosts staring into your own soul.

Horseshoe Canyon was added to Canyonlands National Park in 1971, and regulations are in place to protect the images for future generations. Camping is not allowed in the canyon bottom, and pets are forbidden on the trail or in the canyon bottom. Camping is allowed on the canyon rims, and amenities are limited to a vault toilet.

Hiking here is not difficult, but it does involve a steep, 780-foot climb in and out of the canyon on an old Jeep trail. Once in the bottom, trudging through soft sand dunes can be tiresome. It can also be scorching hot, so plan on carrying at least a gallon of water per person.

The best (and most frequently maintained) road to the trailhead is a 30-mile dirt-and-gravel road that cuts east from U-24 opposite the turnoff to Goblin Valley State Park. Once you are on Interstate 70 west of Green River, take U-24 exit toward Lake Powell. The turnoff is signed.

To learn what archaeologists do and do not know about Horseshoe Canyon, visit the Natural History Museum of Utah website (NHMU.utah.edu) and search for Horseshoe Canyon. Hiking and camping information is available at NPS.gov/cany/planyourvisit/horseshoecanyon.htm .

Jerry D. Spangler is an archaeologist and executive director of the Colorado Plateau Archaeological alliance, an organization dedicated to the preservation of archaeological sites on public lands.