Utah’s beloved public lands bear embracing.

Beyond the quirky cultural landscape of the metropolitan areas that hug the western slopes of the Wasatch Range are great swaths of open land. There are pockets of geographic and archaeological peculiarities shaped by cataclysmic events, carved out by the knife of time. This exceptional place we call home has been scattered with vast public lands to explore, yet how well do we know those areas? How often do we take advantage of what they offer?

As a state with a cultural identity rooted in outdoor recreation and as one with the second-highest percentage of federal lands (after Nevada), Utah is, by nature, an enigma. It not that surprising to overhear someone whisper, “I’ve never actually been there” while protesting at a Bear’s Ears rally. Or when discussing Utah’s treasure trove of outdoor destinations, it’s not uncommon for someone to say, “I was born here and have never heard of that place.”

Given the sheer volume of federal and state land designations in Utah, many of us are just plain bewildered when it comes to knowing where to go and how to best use these lands that belong to one and all.

But for as long as public lands remain a hot-button debate topic, we owe it to ourselves to embrace them—and reclaim them with a broader understanding. Introduce yourself to the public lands within your reach and take advantage of the gift of nature, history and/or culture that they afford.

What’s at stake

Nature might have needed eons to carve out Utah’s lands, but politicians only needed the time it took for a pen stroke to determine their fate. Over the decades, legislation, acts of Congress and presidential orders have set aside 33 million acres of Utah’s 52.7 million acres, accounting for 63 percent of the state’s land. These acres, their terrains and possibilities, have long been mired in controversy regarding their preservation, management and development.

The argument can be broken down into two opposing visions—to relinquish public lands or protect them. Balancing the two is a delicate act. Not only did the disposal of public lands through the Homestead Act of 1862 allow for white settlement in Utah, but the protection of lands led to the creation of five national parks and 45 state parks within the state’s borders.

Consider the four major federal agencies that manage public lands, often in conjunction with one other, and the question of whether these lands should be managed for the interest of the nation or the states. The divisive debate is one from which we might never actually see the dust settle.

At this point in Utah’s history, though, we still have fresh vistas to take our breaths away, rocks to climb and rivers to fish. Our public lands boast archaeological relics aplenty, the best free campsites and a lifetime supply of family vacation destinations. And, hopefully, by embracing these lands, we’ll develop an appreciation for the outdoors and Utah’s unique offerings.

Of 13 types of federal land terms—all with their own prescribed uses and reasons for designation—Utah has 10. It’s important to remember that these lands are owned as much by a brother in the Bay Area as they are by a sister in the Twin Cities; and Utahns are lucky enough to have them in their very own backyard.

UNIQUE ECOSYSTEMS Joshua trees and chollas stand before the snowcapped peaks of Beaver Dam Wash National Conservation area, one of two National Conservation Areas in Utah dedicated to protecting the Mojave Desert tortoise.

NATIONAL PARKS

These iconic areas, managed by the National Park Service, are the most visited public land. Utah’s tourism industry is centered around these parks, created by Congress to protect natural and/or historic features. Utah’s five national parks—Zion, Bryce, Canyonlands, Arches and Capitol Reef—are each a paradise for sightseers and hikers, offering visitor centers, guided interpretive tours with park rangers, gift shops and well-developed, pay-per-night campsites.

NATIONAL FORESTS

National forests offer everything from permit-based timber harvesting and mineral extraction to livestock grazing, wildlife and watershed protection, and recreational access. Usually less crowded than national parks, Utah’s six national forests—Ashley, Dixie, Fishlake, Manti-La Sal, Sawtooth and Uinta-Wasatch-Cache—afford free camping, unpopulated trails and a more primitive experience in nature. Maps, campfire permits and information on the dos and don’ts are available at national forest offices.

LANDS OF MANY USES

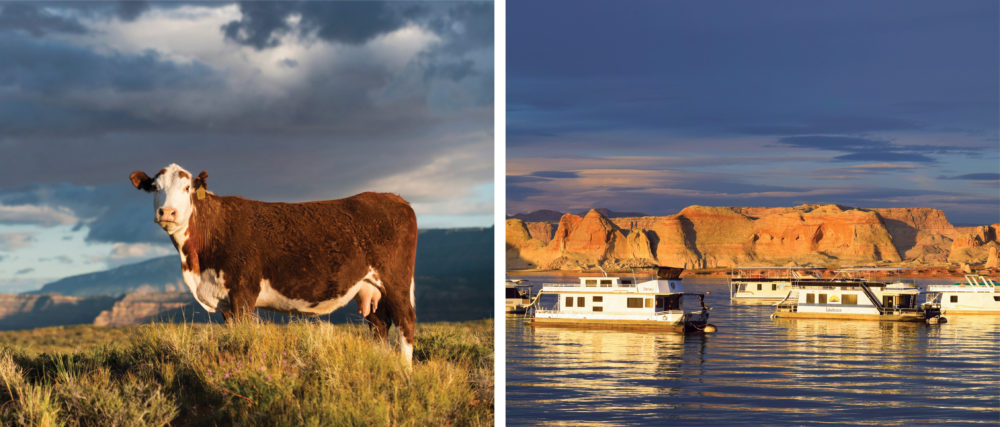

A cow grazes outside of Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, while houseboats float at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.

NATIONAL RECREATION AREAS

Located exclusively near large reservoirs, these public lands are water-sports meccas that also provide water and power to surrounding areas. Utah’s two protected areas—Glen Canyon and Flaming Gorge—offer a bit of everything from fishing for trophy-sized lake trout in Flaming Gorge to summertime houseboat parties in Glen Canyon.

NATIONAL MONUMENTS

National monuments can be created under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to protect archaeological relics and promote understanding of their historic and cultural relevance. Utah’s eight national monuments include Bears Ears (aka Shásh Jaa), Cedar Breaks, Dinosaur, Grand Staircase-Escalante, Hovenweep, Natural Bridges, Rainbow Bridge and Timpanogos Cave, these places offer the unique opportunity to reconnect with the lands and the civilizations that once inhabited them.

NATIONAL WILDERNESS AREAS

Designated by Congress under the 1964 Wilderness Act, these areas, according to the act, are “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Utah is home to 31 such protected areas (Mount Nebo Wilderness Area among them) to ensure their pristine wild lands and fragile ecosystems remain intact. Primitive backcountry camping is permitted, though travel is restricted to foot or horseback.

NATIONAL CONSERVATION AREAS

These public lands are set aside to conserve and protect ecological, cultural and scientific interests. In the case of Utah’s two areas—Red Cliffs and Beaver Dam Wash—management is centered around protecting the Mojave Desert tortoise, a species that is considered threatened on the endangered species list. Recreational uses of these areas are determined by the resiliency of the habitats they protect, but both offer hundreds of miles of scenic hiking trails, rare wildlife-viewing opportunities and a glimpse into unique ecosystems.

NATIONAL HISTORIC SITES

These public lands highlight the people and activities that helped shape the nation. Utah’s sole contender for this designation is the Golden Spike National Historic Site, encompassing 2,735 acres. The site’s visitor center offers a robust history lesson about the West, with locomotives in action for public viewing and re-enactments of driving the final spike and chronicling the completion of the first transcontinental railroad.

NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGES

Developed and managed to foster healthy populations of fish and wildlife, Utah is home to three national wildlife refuges, including Bear River Migratory Bird, Fish Springs and Ouray. Wildlife watching and photography are key activities, while hunting, fishing and trapping are part of each area’s population management plans.

NATIONAL TRAILS

Utah’s 18 National Recreation Trails contribute to the health, conservation and recreation goals of its people. They range from world-class mountain biking on the Moab Slickrock bike trail to Nordic skiing on the Historic Union Pacific Rail Trail between Park City and Echo Reservoir. You can also explore Utah’s 583 miles of the California, Old Spanish and Pony Express national historic trails.

INTERSECTIONS OF SPACES

Riders cruise along the Moab Slickrock bike trail outside of

Arches National Park with the Manti-La Sal National Forest in the background.

As such, many public lands flank one another, adding proximity to their list of benefits.