The petroglyphs of Vernal’s McConkie Ranch evoke mayhem and mystery.

Few travelers see Vernal as a tourism destination—and with hundreds of square miles of oil and gas wells in every direction, it is easy to see why.

But if you love ancient Native American rock art, Vernal is not only a destination but a mecca for some of the finest examples of indigenous rock art anywhere in the world. National Geographic once called the images here the Louvre of America’s native art.

If you’ve never heard of the famed rock art, it’s not all that surprising. Most of the very best concentrations of images are located on inaccessible private lands, and the ones in the famed Cub Creek district of Dinosaur National Monument are more difficult—and remote—to find over a brief weekend visit if you don’t know exactly where to look.

One exception to the “can’t go there, can’t find it” conundrum is the McConkie Ranch, located in what is commonly referred to as the Ashley-Dry Fork about 10 miles northwest of Vernal. There are hundreds of images here that will make your jaw drop and your brain swirl.

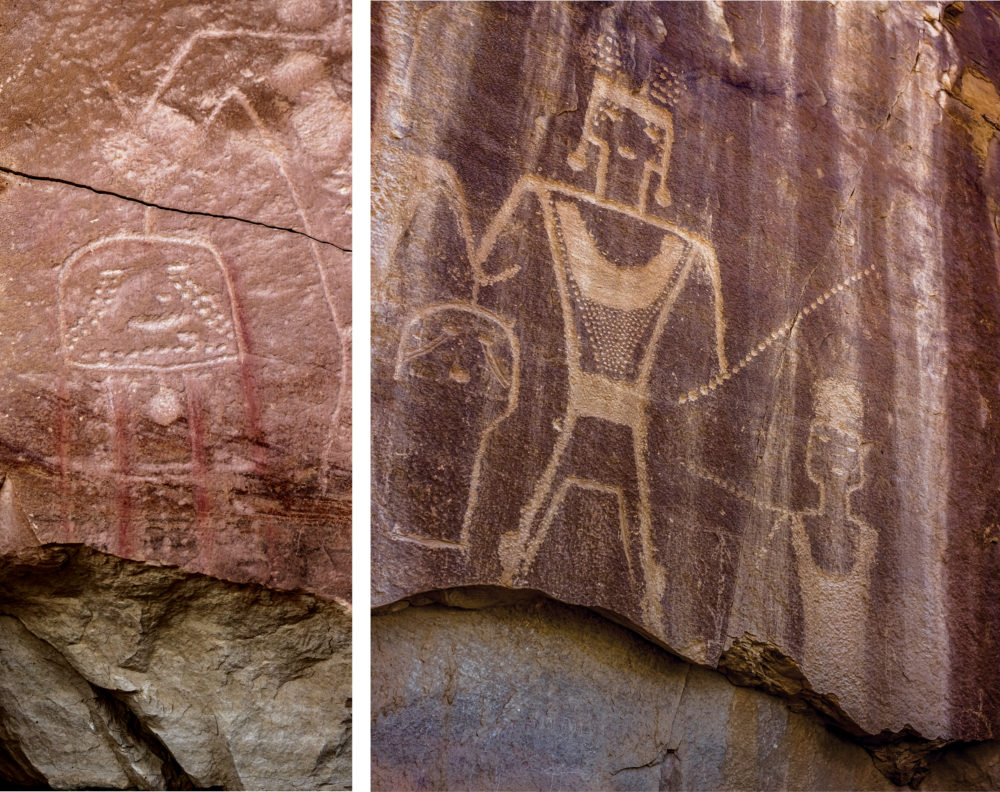

It is not the remarkable precision reflected in the images painted and pecked into the sandstone, but rather bizarre—some might say macabre—subject matters that are depicted. Some of the images seem to depict nearly life-sized humans holding decapitated heads, complete with red paint that has all the trappings of dripping blood.

It is not surprising that these images have led many to speculate the ancients here were “headhunters” and the compositions depict actual events where enemies were ceremoniously dispatched to the afterlife.

Maybe, maybe not. Archaeologists are always wary of projecting our literalist modern view onto the ancients who might have viewed the world in abstract or surreal terms. Quite simply, there is no way for us today to know what was in the minds of the people who made those images.

But if the purpose of art is to make people think, then the McConkie Ranch artists succeeded many times over. It is impossible to come away from the experience with indifference. You might be revolted at the thoughts that creep into your head—or awed at the remarkable attention to detail: the eyes looking back at you, the jewelry, the hairstyles, the depictions of what seem to be husbands with their wives, the shields suggesting these were dangerous times, the tears.

Whatever the images evoke, you will come away feeling something.

Who were these ancient artists? Archaeologists refer to them as the Fremont Complex, which is an umbrella term for all of the ancient farmers of Utah between about 250 AD to 1300 AD. They might have belonged to different ethnic groups, spoken different languages, and relied on maize farming to differing degrees. But they all shared one trait: rock art.

The Fremont people typically depicted human figures with rigid trapezoidal shapes (wider at the shoulders than the waist), although there is lots of variation from one region to the next. The famous rock art of Nine Mile Canyon and Capitol Reef and the San Rafael Swell are all attributed to Fremont people. In the Vernal area, the rock art reached an unprecedented level of precision and detail not found anywhere else in Utah.

These artists even mastered rare technique called “bas relief,” where the stone was removed from around the image to leave the image itself projecting from the cliff face as a sort of sculpture. Not only is this difficult to do with metal tools, it would have been unimaginably difficult with primitive stone tools.

Based on the radiocarbon dates from ancient houses in the McConkie Ranch area, these images were probably made by early farmers. The first farmers arrived about 250 AD and might have been immigrants from the San Juan River area in the Four Corners. They might have intermixed with local populations to produce the unique hybrid we call the Fremont today. By about 1000 AD they had moved to other areas in the Uinta Basin, and some might have persisted as late as 1500 AD in the Flaming Gorge area and in northwestern Colorado.

But for seven centuries or more, they pecked and painted their view of a remarkable world on the cliff walls in northeastern Utah where they continue to evoke wonder and awe.

To reach the McConkie Ranch, drive north of 500 West in Vernal and stay on the road until you reach the town of Maeser. Turn north on 3500 West and follow the road into Dry Fork Canyon. The turnoff to the ranch is well marked.

Remember to always respect private property here. The owners have graciously allowed visitors to wander the trails, and they keep it open through voluntary donations. Please be generous so that they keep it open for future visitors.

The main trail open to visitors is a little over 3/4 mile out and back. Also ask for permission to visit the Three Kings—perhaps the most impressive of all the rock art panels. It is not located on the main visitors trail but rather next to the road below the small visitors’ center.

Jerry D. Spangler is an archaeologist and executive director of the Colorado Plateau Archaeological Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving archaeological and historic sites on public lands. Photos for the story are provided by Dan Bauer and Mark Byzewski.